Afternoon my lunchtime amigos.

This is coming a little late as I was fighting for my life against the zombie cold that seems to have struck everyone in New York. While I was rotting in bed reading the Fourth Wing series (we all need to nest and recuperate, my chosen form is binging with unreserved joy whatever cliche Romantasy novel booktok has thrown my way), my few productive thoughts were parsing over this surging Surrealism I seem to find around every corner. I’m not talking about the weird headlines on geopolitics (is someone going to check on Elon’s Ketamine usage?) I mean it in the cultural, daily life sphere that we come across as we walk around the city.

In fashion — Schiaparelli has single-handedly revived a depressingly dull haute couture landscape.

In auctions — Latin American female Surrealists have invigorated an Impressionist and Modern market, which previously couldn’t have been revived if Zeus struck it with a lightning bolt.

Also in auctions — Magrittes are single-handedly saving sale numbers in the London auctions.

In museums — museums from Brooklyn to Bilbao have embraced a Surrealist renaissance, retrospectives abound! (Ok, this at least is explainable because it is the centennial of the movement)

But still what gives??

Even dinner parties have caught the wave—and would like to proudly (annoyingly) point out I was ahead of the curve and hosted the legendary Surrealist dinner party (pictured below) in January 2024. Artnet published an article covering Dali-inspired soirées as the latest theme du jour.

Emerging artists, too, like Meghann Stephenson, as we discussed a couple of weeks ago, are mining classic Surrealist veins and reinterpreting them for a distinctly 21st-century sensibility.

So what gives? Why is Surrealism, of all movements, suddenly feeling fresher than your local farmer’s market heirlooms?

My theory, briefly put, is that the surreal has become indistinguishable from reality. Headlines oscillate wildly between farce and dystopia; markets behave with seeming irrationality; and AI-everything has permanently altered our tolerance for—and familiarity with—the uncanny.

Surreality is now our baseline. And because familiarity breeds affection (recall that rather depressing study linking geographical proximity to romantic attraction), the once-unsettling weirdness of Surrealism now feels reassuringly homey.

And where attention goes, money flows.

So, money is flowing into Surrealism because it is familiar and we keep paying attention to it. Walk with me down this path.

The last moment the melting clock was on time

Surrealism has always flourished during times of profound upheaval, emerging in postwar Paris amid the psychic rubble of the Great War and resurging in the early 1970s during another era of geopolitical tremors.

Specifically, consider 1972: The U.S. was riding the tail end of a postwar economic boom, with GDP growth still relatively healthy, unemployment not yet alarming.

This created a curious moment of optimism, even as there were clouds on the horizon: Nixon had ended the Bretton Woods system the previous year (closing the gold window in 1971), the full force of the 1973–1974 downturn and oil embargo was still waiting in the wings, inflation was slowly creeping up, and tensions around Vietnam were inescapable.

But for many, this peculiar interlude was when affluent society merrily danced on the deck of the Titanic, buoyed by the Nifty Fifty stock phenomenon. Among affluent investors, there was a powerful story circulating about “can’t lose” growth stocks—companies like IBM, Coca-Cola, and Polaroid. The narrative was that these large, high-quality firms were practically guaranteed winners: buy and hold forever.

Sounds like something familiar? Magnificent-7 anyone?

It wasn’t all glitter and gold though. Not front-page news for the average consumer, Nixon’s decision in 1971 to end dollar-gold convertibility loomed large in elite financial circles. Freed from the old gold peg, currency values became more volatile. While some saw this as a chance to speculate on currency markets or pivot to real assets (like real estate, farmland, or yes, even art), others worried about the shaky underpinnings of a global monetary system in transition.

Still, as inflation had not yet roared into everyday life, these concerns simmered rather than boiled over. The narrative here was the promise of a more flexible, “modern” monetary order—enough to fuel confidence that the U.S. could control any inflationary blips.

Again history does not repeat, it rhymes. Someone should tell the Fed.

It is this backdrop of shaky foundations for unstoppable confidence that the Rothschilds hosted their infamous Surrealist Ball. Such uncertainties felt comfortably remote.

In the language of Pierre Bourdieu, Surrealism had transformed itself from avant-garde provocation to glamorous cultural capital—a tasteful indulgence, perfectly calibrated for an elite whose confidence had not yet encountered the sharp correction of 1973’s oil embargo and market collapse. This was the year before a more sobering reality would set in.

By 1973–1974, inflation skyrocketed, the market crashed, and Watergate consumed the White House, upending that cheery story of perpetual prosperity.

But for a brief window in ’72, the dominant narrative was still: “We’ve got this.”

Why Surrealism Feels Right at Home in Our Uncertain Age

Today, our parallels with that era are impossible to miss. We’re facing another unravelling of geopolitical certainties: Trump back in the Oval Office, Musk shaping global diplomacy from Twitter threads, and alliances thought eternal (the US-Canada partnership, EU solidarity) suddenly fraying like the seams of a Shein haul after a single wash.

Against this backdrop of anxious volatility, Surrealism’s dreamlike distortions feel utterly familiar. Just as Dalí and Magritte thrived in uncertain times by making the absurd aesthetically pleasurable, today’s collectors find reassurance in Surrealism’s ability to reflect the weirdness of the everyday back at us, polished and profitable.

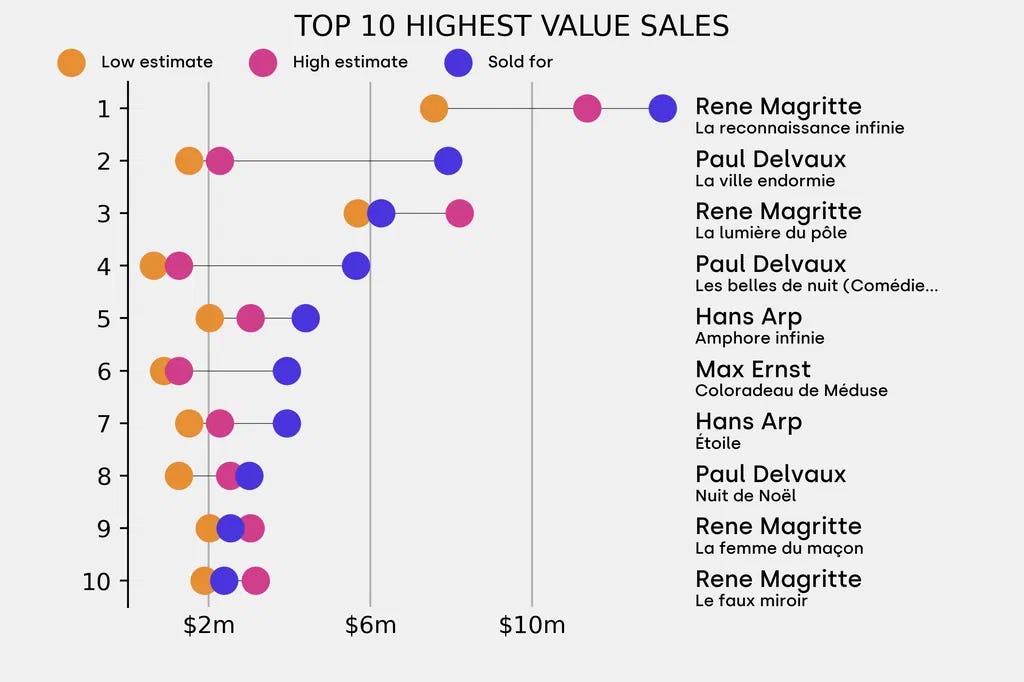

The recent auction market underscores this phenomenon. Sotheby’s and Phillips stumbled embarrassingly in their March London sales, burdened with "overpriced Picassos and uninspired Basquiats nobody wanted," as delightfully reported by Frame and Flame.

Christie's, however, thrived precisely because it embraced Surrealism: Magritte led the charge, flanked by Delvaux and de Lempicka—artists whose work provides both the thrill of cultural edginess and the reassurance of historical legitimacy.

Collectors weren’t just buying art; they were buying stability disguised as avant-garde subversion.

Ceci n’est pas une Distraction

Yet today's resurgence is turbocharged by something even André Breton himself couldn’t foresee: the attention economy. Herbert Simon warned us decades ago about the true scarcity in modern life—our limited capacity for attention.

Surrealism, with its uncanny visuals and vivid dreamscapes, excels at seizing and holding gaze in our fractured, media-saturated age. Our collective appetite is primed for the surreal. Everywhere you turn you see Trumpian sequel politics, Musk’s extraterrestrial sway on earthly affairs, and daily doses of AI-generated weirdness, surreal images speak a comforting truth: things have always been this strange; we’re just finally admitting it.

Since our brains reward the familiar, I can see why Surrealism’s keeps getting airtime.

It’s so familiar, we inherently understand it and so we keep looking at it.

Come in with the chorus now: “Where attention goes, money flows”

Robert Shiller’s concept of narrative economics reminds us that compelling stories shape financial decisions as much as rational analysis. Story goes that compelling stories and widely shared beliefs significantly shape economic decisions more than rational analysis or hard data alone.

This begs the question - what stories are we telling ourselves today that make Surrealism so compelling?

At the macro level, inflation is no longer raging, but interest rates are still elevated, limiting easy money. At the global level, new conflicts and alignments push HNWIs to become more resourceful, seeking cultural assets (like “blue chip” Surrealist art) and more stable regions to park their wealth.

The overarching vibe is reminiscent of the early 1970s’ sense that the postwar consensus is kaput—only now, everything moves faster and more loudly thanks to digital hyper-connectivity.

Much like in 1972, there’s a willful optimism in some corners—tech breakthroughs, stable-enough job numbers—but it’s overshadowed by the creeping knowledge that the world order might be pivoting toward something entirely different.

Psychologically, that means a persistent undercurrent of risk-aversion, an emphasis on safe cultural bets, and a resigned sense that, while a meltdown isn’t guaranteed, the old certainties are irretrievably gone.

When money is expensive, why is 'weird' worth the price?

To put a finer point to it: Why has Surrealism—once proudly destabilizing—become the risk-averse darling of cautious investors?

I look at Art investment as a cultural barometer. In anxious times the market reveals intriguing connections between psychological absurdity and financial prudence.

Even with reassuring economic indicators—falling inflation, low unemployment—consumer confidence today remains stubbornly low. Why? Because money simply feels expensive. Larry Summers and co. point to high borrowing costs, and while the collector buying a $10 million Magritte isn’t fretting about interest rates for that particular acquisition—but they're certainly assessing their broader portfolio.

With money’s psychological cost higher, even the ultra-rich scrutinize their expenditures more closely, favoring assets that promise resilience through uncertain periods.

Thus, Surrealism’s recent ascent. Once provocative Surrealism has fully institutionalized. Tamed. De-clawed even, if I was trying to start a fight.

It's even trickling down, experiencing a distinctly mainstream “Monet moment.” Universally agreed upon as ‘good art.’ If you're splurging for cultural capital, Surrealism offers just enough stability to seem sensible and just enough weirdness to stay interesting—exactly what's required to hold value in uncertain times where value is dominated by who can keep the eyeballs.

This applies to both those buying Magrittes or hosting a dinner party.

The Economics of Weirdness: Why Surrealism Commands a Premium

Scarcity used to mean something simple—rare gems, limited editions, the last decent table at Balthazar. Now, it’s about the capacity to grab attention in an age defined by chronic distraction.

Surrealism was designed to do just that. Pry into the recesses of your subconscious and stop you in your tracks. The investors have cottoned on – they’ve discovered the movement’s uncanny ability to freeze scrolling thumbs mid-air—an advantage no algorithm can fake.

Attention, as it turns out, isn’t just valuable—it’s the new gold standard.

With economic decisions hinging more on storytelling than spreadsheets. Today we don’t just accept absurdity—we expect it. With geopolitical fiascos, tech bro drama, and headlines fit for satire, our tolerance for chaos has never been higher. Surrealism, once avant-garde provocation, now offers both emotional relief and economic reassurance. It’s strange enough to keep us entertained, yet institutional enough to keep investors from losing sleep.

The cultural set’s gatekeepers—auction houses, gallerists, fashion designers—aren’t cynically cashing in (or at least not entirely); they’re intuitively responding to a cultural market that prizes the arresting and unusual.

Embracing weirdness thus becomes less about irrational indulgence and more about strategic foresight, betting confidently on future cultural tides.

I'm curious: I have been seeing quite a few people (even outside of strictly academic/medievalist circles) argue for a type of "neo-Medievalism" pervading culture and economics. The consolidation of wealth among a wealthy few, an "indentured" peasant class forced to rent land to produce value for the elite, and the rise of almost "Sturm und Drang" emotional discourse in art/literature pervading cultural spheres seem to indicate this return--not to mention the considerable interest in medieval aesthetics that have been dominating television and movies for the past decade! Is this moment of surrealist revival part and parcel of a "neo-Medievalism"?

Thank you for this insight. To call today’s artistic movement neo-surrealism—or even surrealism—doesn’t quite capture what’s happening, and even artists are missing the mark. During the French Revolution, realism was dominant. Between WWI and WWII, and in the aftermath, surrealism and Dada resonated deeply, but they also failed in many ways. Artists like Hannah Höch and many others were underrepresented, while Freudian, often misogynistic, themes were rampant.

Today, we are more visually and intellectually nuanced. Postmodernism was not the final word. We are in an age of infinity—not borrowing from the past as a simple neo-movement, but rather correcting, reinterpreting, and expanding upon it. What we are achieving in relation to surrealism is not surrealism. It is not Duchamp’s anti-art. It is something deeper—a movement toward truth. It functions like an elevator in and out of Plato’s cave, shifting between illusion and reality with greater awareness.